This article was extracted from “IN THE JOURNAL OF NUTRITION, jn.nutrition.org”

Traditional Soyfoods: Processing and Products (note 1)

PETER GOLBITZ (note 2)

Soyatech, Inc., Bar Harbor, ME 04609

ABSTRACT Although soyfoods have been consumed for more than 1000 years, only for the past 15 years have they made an inroad into Western cultures and diets. Soyfoods are typically divided into two categories: nonfermented and fermented. Traditional nonfermented soyfoods include fresh green soybeans, whole dry soybeans, soy nuts, soy sprouts, whole-fat soy flour, soymilk and soymilk products, tofu, okara and yuba. Traditional fermented soyfoods include tempeh, miso, soy sauces, natto and fermented tofu and soymilk products. This paper presents a brief overview of processing techniques used in the manufacture of traditional soyfoods. J. Nutr. 125: 570S-572S, 1995.

For more than 1000 years, people throughout Asia have been consuming soybeans in a variety of traditional soyfood products. Only for the past 15 years have soyfoods begun to make a significant inroad into Western cultures and diets.

There are many types of soyfoods available throughout the world today. Some are produced through the use of modern processing techniques in large soybean-processing plants, whereas others are produced in more traditional ways, owing their history to Oriental processing techniques. These are the foods that are usually referred to as traditional soyfoods.

These soyfoods are typically divided into two categories: nonfermented and fermented. Traditional nonfermented soyfoods include fresh green soybeans, whole dry soybeans, soy nuts, soy sprouts, whole-fat soy flour, soymilk and soymilk products, tofu, okara and yuba. Traditional fermented soyfoods include tempeh, miso, soy sauces, natto and fermented tofu and soymilk products.

Westerners have adopted some of these foods wholeheartedly, whereas others will undoubtedly take more time to accept. The most popular soyfoods in the United States now are tofu, soymilk, soy sauce, miso and tempeh. Americans, known for their ability to adapt foreign foods to their own tastes, have developed a whole new class of “second generation” soyfoods, which includes such products as tofu hot dogs, tofu ice cream, veggie burgers, tempeh burgers, soymilk yogurt, soymilk cheeses, soy flour pancake mix and a myriad of other prepared Americanized soyfoods.

Largely because of the great entrepreneurial spirit of many small American companies, sales of soyfoods in the United States have been growing steadily since 1980 and are projected to reach the one billion dollar level by the year 2000 (Golbitz 1991a). Only recently have larger food companies realized the potential of the soyfoods market and begun distribution of soybean-based veggie burgers in American supermarkets (Golbitz 1992).

This paper is intended to serve as a brief overview of processing techniques used in the manufacture of traditional soyfoods.

Soymilk

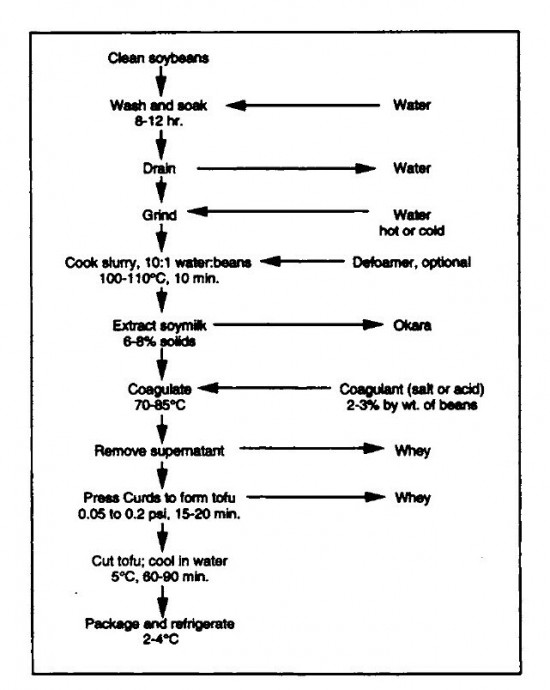

Soymilk is used as a base in a wide variety of products, including tofu, soy yogurt and soy-based cheeses. Soymilk is the aqueous extraction of whole soybeans. Methods of soymilk production are shown in Figure 1.

Particularly important was identifying and inactivating components primarily responsible for the undesirable beany flavor in soymilk. The enzyme believed to be responsible for creating soymilk’s off-flavors is inactivated by using boiling water in the grinding stage of production. The use of a hot water and sodium bicarbonate blanch before grinding also reduces off-flavors. The application of modem dairy processing technologies to the process deodorizes the soymilk, adds whatever flavors are desired and packages the product in sterilized, long-life packages. These innovations were crucial to the development of today’s soymilk products (Shurtleff and Aoyagi 1984).

Note 1. Presented at the First International Symposium on the Role of Soy in Preventing and Treating Chronic Disease, held in Mesa, AZ, February 20-23, 1994. The symposium was sponsored by Protein Technologies International, the soybean growers from Nebraska, Indiana and Iowa and the United Soybean Board. Guest editors for this symposium were Mark Messina, 1543 Lincoln Street, Port Townsend, WA 98368, and John W. Erdman, Jr., Division of Nutritional Sciences, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801-3852.

Note 2. To whom correspondence should be addressed: Soyatech, Inc., 318 Main Street, PO Box 84, Bar Harbor, ME 04609.

FIGURE 1 Methods of soymilk production. SB, cleaned soybeans; DSB, dehulled, cleaned soybeans; RHHC, rapid hydration hydrothermal cooking. Reprinted with permission from Chen 1989.

Tofu

Tofu appeared in American supermarkets around 1980. Supported by many micro- and megatrends, tofu was seen as one of the foods that marked the beginning of a major shift in food-buying habits. Tofutti, an ice cream substitute made with tofu, proved to Americans that a soybean-based food product could actually taste good. In the short span of just 2 years, Tofutti gained national distribution and was mentioned in scores of major news articles and magazines. Tofutti’s acceptance proved to others marketing tofu and tofu products that if you wanted to sell soyfoods to American consumers, you have to give them what they want: ice cream, hot dogs and burgers. Because tofu is relatively bland and can act as a functional food ingredient, it has ended up in hundreds of prepared food products (Golbitz 1991a).

There have been some recent innovations in tofu processing that have helped to support continued market growth. These have primarily been in packaging, with pasteurization adding 30-60 days to the shelf life of refrigerated tofu and aseptic packaging allowing some tofu to be stored for 1 year at room temperature. Shown in Figure 2 are the basic steps used to produce tofu.

Tempeh

Tempeh is a fermented soyfood and is unique in its texture, flavor and versatility. It originated in Indonesia, where today it is still the most popular soyfood (Winaro and Reddy 1986). Tempeh, while not as popular as tofu in the United States, lends itself easily to being used as a meat alternative because of its chewy texture and distinct flavor. As a result, a wide variety of tempeh-based meat analogues are available.

Tempeh is a cake of cooked and fermented soybeans held together by the mycelium of Rhizopus oligosporus. Figure 3 shows the basic processing steps used to produce tempeh. Tempeh can then be further processed or packaged and pasteurized for distribution.

FIGURE 2 Flow chart for regular tofu production. Reprinted with permission from Shurtleff and Aoyagi 1979.

Miso

Miso, a white, brown or reddish-brown soybean paste, is another fermented soyfoods product. Made from fermented soybeans, and sometimes in combination with wheat, barley or rice, this salty paste is a treasured soup base and flavoring ingredient used throughout Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Indonesia and China (Ebine 1986).

There are many types of miso available in the United States today, from sweet white miso to the more savory dark miso. Miso, sold extensively in natural food stores and Oriental markets, has developed a following among New Age cooks and health enthusiasts who savor its rich flavors and believe in its purported healthful benefits.

To produce miso, whole soybeans are soaked in water and cooked until tender. The cooked soybeans are dusted with Aspergillus oryzae—a fungal starter—and shaped into koji nuggets. This can be done in combination with either rice or barley. These nuggets are incubated, during which time the fungus matures on the soybeans causing them to become white and fuzzy. Enzymes and nutrients produced during this stage are essential to later stages of fermentation. The mature nuggets are mixed with salt and water in fermentation vats, resulting in the formation of a paste. During aging, the miso’s flavors and aromas are acquired. When the miso is fully ripened, it is blended, pressed and packaged (Ebine 1986).

FIGURE 3 Flow chart for tempeh production. Reprinted with permission from Winaro and Reddy 1986.

Soy sauce

Soy sauce is probably man’s oldest prepared seasoning. Processed similarly to miso except that the paste produced is pressed to yield a liquid, this savory seasoning sauce is widely used in both Oriental and American cuisine (Nunomura and Sasaki 1986).

There are two basic types of soy sauce: fermented soy sauce and soy sauce made from hydrolyzed vegetable proteins (HVP). Within the naturally fermented category, there are many types of soy sauce, with shoyu and tamari being the most popular. For the most part, defatted soybean meal or grits are used to produce soy sauce, with some specialty products being made from whole soybeans. HVP soy sauce is made from soy proteins hydrolyzed into amino acids by using acid hydrolysis and blended with sugars, color and other flavoring ingredients into a sauce that somewhat resembles naturally fermented soy sauce (Nunomura and Sasaki 1986). Soy sauce is also available in flavored forms, catering to Americans’ needs for convenience, ease of use and versatility (Golbitz 1991a).

In many Asian countries soyfoods play a major role in people’s diets. Estimates are that the annual per capita consumption of soybeans, directly and indirectly as soyfoods, in China, Indonesia, Korea, Japan and Taiwan are 3.4, 6.3, 9.0, 10.8 and 13 kg, respectively (Golbitz 1991b).

Best,

Tan Kok Hui

Nutrition Made Simple, Life Made Rich

LITERATURE CITED

Chen, S. (1989) Principles of Soymilk Production, Food Uses of Whole Oilseeds and Protein Seeds. American Oil Chemists Society, Champaign, IL.

Ebine, H. (1986) Legume-Based Fermented Foods. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL.

Golbitz, P. (1991a) Practical Aspects of Marketing Soya Products and Other Ready to Eat Soyfoods. American Soybean Association, Brussels, Belgium.

Golbitz, P. (1991b) Soyfoods Consumption in the United States and Worldwide, A Statistical Analysis. Soyatech, Inc., Bar Harbor, ME.

Golbitz, P. (1992) The Meat Alternative Market and Industry in the United States. Soyatech, Inc., Bar Harbor, ME.

Nunomura, N. & Sasaki, M. (1986) Legume-Based Fermented Foods. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL.

Shurtleff, W. & Aoyagi, A. (1984) Soymilk Industry & Market. Soyfoods Center, Lafayette, Calif. CA.

Shurtleff, W. & Aoyagi, A. (1979) Tofu & Soymilk Production, The Book of Tofu. Vol. II. Soyfoods Center, Lafayette, CA.

Winaro, F. G. & Reddy, N. R. (1986) Legume-Based Fermented Foods. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL.