This article was extracted from “The Official Journal of the Japanese Cancer Association.”

Fermented and non-fermented soy food consumption and gastric cancer in Japanese and Korean populations: A meta-analysis of observational studies

Jeongseon Kim (note 1, 3), Moonsu Kang (note 1), Jung-Sug Lee (note 1), Manami Inoue (note 2), Shizuka Sasazuki (note 2) and Shoichiro Tsugane (note 2)

(note 1. Cancer Epidemiology Branch, Research Institute, National Cancer Center, Goyang, Korea); (note 2. Epidemiology and Prevention Division, Research Center for Cancer Prevention and Screening, National Cancer Center, Tokyo, Japan)

Soy food is known to contribute greatly to a reduction in the risk of gastric cancer (GC). However, both Japanese and Korean populations have high incidence rates of GC despite the consumption of a wide variety of soy foods. One primary reason is that they consume fermented rather than non-fermented soy foods. In order to assess the varying effects of fermented and non-fermented soy intake on GC risk in these populations, we conducted a meta-analysis of published reports. Twenty studies assessing the effect of the consumption of fermented soy food on GC risk were included, and 17 studies assessing the effect of the consumption of non-fermented soy food on GC risk were included. We found that a high intake of fermented soy foods was significantly associated with an increased risk of GC (odds ratio [OR] = 1.22, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.02–1.44, I2 = 71.48), whereas an increased intake of non-fermented soy foods was significantly associated with a decreased risk of GC (overall summary OR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.54– 0.77, I2 = 64.27). These findings show that a high level of consumption of non-fermented soy foods, rather than fermented soy foods, is important in reducing GC risk. (Cancer Sci 2011; 102: 231–244)

Gastric cancer (GC) is the most common cancer in Japan and Korea and the second leading cause of death from cancer globally, although the incidence and mortality have been declining over the years.(1) Dietary factors are known to play an important role in the development of GC.(2) Among dietary factors, soy has been of considerable interest in the etiology of GC.(3) It is widely known that soy foods may help reduce the risk of developing GC. This might be due to the fact that soy foods are good sources of isoflavones, which are antioxidants known to reduce the risk of GC.(3) However, despite the fact that Japanese and Korean populations generally have a high intake of soy foods, they also have a higher risk of GC than other populations, including those in the USA and Europe.

This might be explained by the fact that Japanese and Korean populations consume more fermented soy foods than non-fermented ones. Common fermented soy foods, which generally contain a high content of salt, include soy paste and fermented soybeans.(3) The most common non-fermented soy foods include soymilk, tofu, soybeans and soy nuts. There is a contradictory relationship between the intake of soy food and GC; GC risk increases with the intake of fermented soy foods and decreases with the intake of non-fermented soy foods.(4) Fermented soy may offer health benefits due to the fermentation process. However, it may have adverse effects on GC risk due to high levels of nitrate or nitrite, large amounts of salt, and the loss of key nutrients under acidic and oxygenic conditions.

An extensive meta-analysis of the relationships between fermented soy foods and GC risk has not been conducted. Thus, we carried out a meta-analysis of the relationships between the consumption of fermented and non-fermented soy foods and GC risk in Japanese and Korean populations.

Materials and Methods

Selection of studies for the meta-analysis. We searched the reference lists of publications concerning diet and GC conducted in Japanese and Korean populations. The search engines used for this study included PubMed, KoreaMed and Ichushi. We used the following keywords: “gastric cancer” or “stomach cancer”, “soy”or “fermented soy”, and “Japan” or “Korea”. We also searched the references cited in the articles and included published works written in Japanese, Korean and English.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria. The inclusion/exclusion criteria for this meta-analysis were as follows:

- Only results that specified the food item studied was “fermented soy”, “non-fermented soy” or were included. The term “fermented soy” included miso (soup) or soybean paste (soup or stew), while “non-fermented soy” included tofu, bean curds or non-fermented soy (bean) products.

- Only subjects who were Japanese or Korean, including migrants, were included.

- Cohort or case–control studies were included. Reviews and meta-analyses were excluded.

- We excluded case–control studies that presented mortality rather than GC incidence.

- The studies that included adjusted 95% confidence intervals (CI) and either a relative risk (RR) or odds ratio (OR) were included for meta-analysis. We excluded studies that did not present an adjusted 95% CI or those that showed regression coefficients.

- When multiple studies were published on the same subject population, we included only the most recent study.

Data abstraction. Two reviewers independently examined the studies for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by consensus. We collected the following information from each study: study design, author, publication year, nation, study period, study subjects (type and sources, definition and numbers of subjects), category of food intake from the lowest to the highest, RR/OR and 95% CI, P for trend, and confounding variables.

Statistical analysis. In order to adjust for the confounding factors and to include those studies with missing values (cross-tabulation) in the tables, we used an unconditional logistic regression analysis to compute the RR or OR with a 95% CI. We assessed statistical heterogeneity across the studies by calculating the variation between studies (s2) from the Q statistic. Based on these results for heterogeneity, we used either a fixed-effect or random-effect model to compute the summary OR and 95% CI. For assessing publication bias, asymmetry was tested using Begg’s funnel plot. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. We carried out all analyses using STATA 10 software (STATA, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

We identified a total of 69 articles in the initial computerized search of published work. After screening the articles according to title and abstract, 43 articles (two review papers, one meta-analysis, 27 experimental studies or clinical trials, two studies of populations from countries other than Japan or Korea, four studies with the same subject population, and seven studies on other foods, soy foods or non-dietary factors) were excluded. Twenty-two articles (nine cohort studies(2,5–12) and 13 case–control studies(13–25)) assessing the effect of consumption of fermented soy foods on GC risk were included in the meta-analysis. Eighteen articles (six cohort studies (2,9–11,26) and 12 case–control studies (15,16,18–20,22–25,27–29)) assessing the effect of consumption of non-fermented soy food on GC risk were included in the meta-analysis.

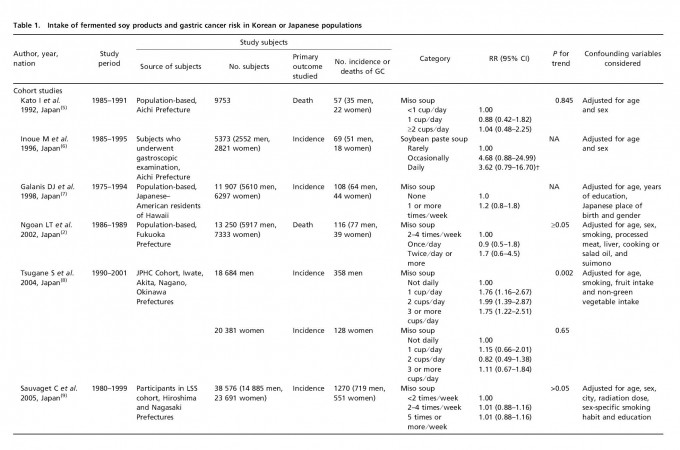

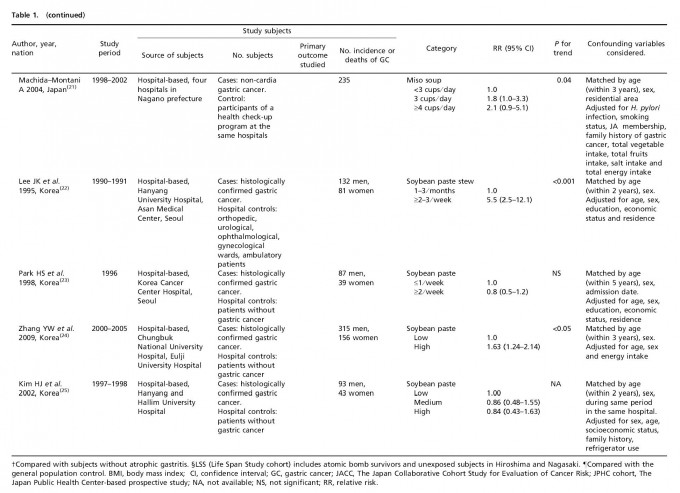

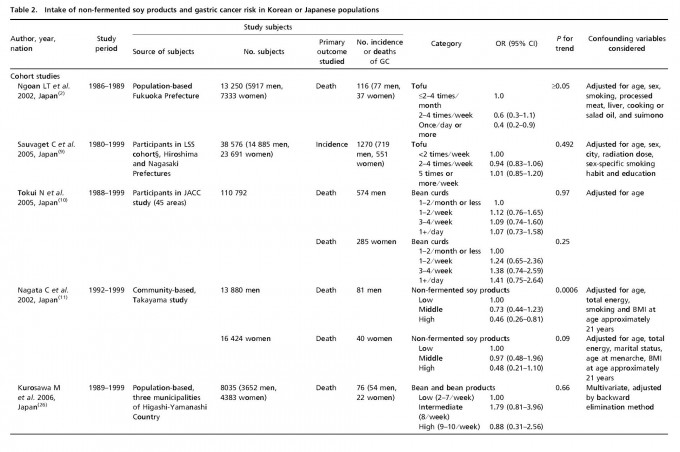

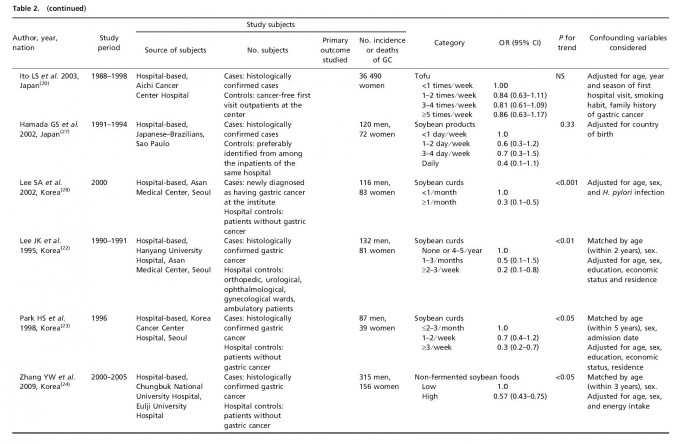

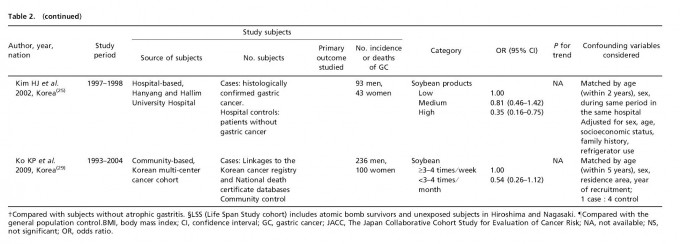

Table 1 lists the included cohort and case–control studies on the effect of fermented soy products on GC risk. Similarly, Table 2 lists the included cohort and case–control studies on the effect of non-fermented soy products on GC risk. Most studies adjusted for confounding factors, including age and sex. We obtained statistically significant results when testing for hetero-geneity between studies of fermented soy foods (overall summary Q = 98.18 with 28 degrees of freedom (df), P < 0.001; cohort studies Q = 27.36 with 11 df, P = 0.004; case-control studies Q = 66.51 with 16 df, P < 0.001) and non-fermented soy foods (overall summary Q = 61.58 with 22 df, P < 0.001; cohort studies Q = 18.07 with eight df, P = 0.021; case-control studies Q = 30.08 with 13 df, P = 0.005). Therefore, we selected a random-effect model to produce the summary statistics. The results of the meta-analysis of the relationships between GC risk and non-fermented soy food intake and fermented soy food intake are summarized in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. A high intake of non-fermented soy foods was significantly associated with a decreased risk of GC (overall summary OR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.54–0.77, j2 = 64.27; cohort studies OR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.60–1.13, j2 = 55.73; case–control studies OR = 0.57, 95% CI = 0.46–0.71, j2 = 56.78), whereas a high intake of fermented soy foods was significantly associated with an increased risk of GC (overall summary OR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.02–1.44, j2 = 71.48; cohort studies OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 0.88–1.41, j2 = 59.79; case–control studies OR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.04–1.73, j2 = 75.94). In order to assess for publication bias, Begg’s funnel plot(30,31) for the assessment of publication bias is presented in Figure 3 for fermented soy food and in Figure 4 for non-fermented soy food. The funnel plots did not detect a publication bias in the meta-analyses of the effect of fermented (Z = 0.11, P = 0.910) or non-fermented soy foods (Z = 0.95, P = 0.342) on GC risk.

Discussion

Soy food has been a major plant source of dietary protein for Asians, especially Japanese and Koreans, and many epidemio-logical studies suggest that soy intake may be a strong protective factor against cancer in humans.(32 Soy food consumption might help reduce the risk of various cancers, including breast cancer, colon cancer, colorectal cancer and gynecological cancer.(3,32–39 However, although soy foods were among the specific food items assessed in the studies included in this meta-analysis, few of the investigators discussed their findings on soy consumption in connection with GC risk.

Fig. 3. Begg’s funnel plot for fermented soy foods in case–control studies and cohort studies.

Fig. 4. Begg’s funnel plot for non-fermented soy foods in case–control studies and cohort studies.

In the present study, a high intake of non-fermented soy food decreased GC risk (overall summary OR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.54–0.77; cohort studies OR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.60–1.13; case–control studies OR = 0.57, 95% CI = 0.46–0.71). Soy has a protective effect against GC.(40) Compared with other plant food sources,(34) non-fermented soy foods are an abundant source of isoflavones, including genistein and daidzein,(41) which are primary anticancer elements in soy. They may block the intragastric formation of carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds.(42,43) Genistein has been shown to inhibit the growth of GC cells.(44) In addition, genistein lessens gastric carcinogenesis by increasing apoptosis and decreasing cell proliferation and the angiogenesis of antral mucosa and GC.(45) Other components in soy foods may also be important anticancer agents.(11)

It has been noted that the form and sources of isoflavones might change the association between soy isoflavones and cancer risk.(46) The dietary habits of Korean and Japanese people are characterized by a high intake of salty foods and carbohydrates, and a higher intake of cooked rather than fresh vegetables.(25) Increases in the risk of GC associated with a high intake of fermented soy foods have been reported in epidemiological studies among Koreans,(22,47) Japanese,(15,48) Taiwanese(49) and Chinese(50) populations. The GC risk increases with the consumption of fermented soy foods and decreases with the consumption of non-fermented soy foods.(4) In other words, the effect of soy foods on the risk of GC differs depending on the preparation of the soy food.

In our study, a high intake of fermented soy food, such as soybean paste and stews, was significantly associated with an increased GC risk (overall summary OR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.02– 1.44; cohort studies OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 0.88–1.41; case– control studies OR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.04–1.73). Fermented soy foods generally contain a considerable amount of salt added during preparation or fermentation. Many studies already show that a high salt diet is a risk factor for GC.(22,25,51,52) For example, Koreans have the highest rates of 24-h urinary sodium excretion(47) and one of the highest rates of mortality from GC.(53,54) Salt is not a carcinogen, but consumption of salt and foods preserved in salt might increase (atrophic) gastritis through damage to the gastric mucosa, which then induces DNA synthesis and cell proliferation, leading to GC.(55) Moreover, foods high in salt improve Helicobacter pylori colonization in the stomach.(56) H. pylori infection is associated with an increase in the endogenous synthesis of nitrate in the stomach. It decreases gastric vitamin C concentrations(57) and increases endogenous N-nitroso compound formation. Therefore, a high intake of salt and foods preserved in salt has been considered a plausible cause of GC in many studies.(8,22,26,28,58–60) Antioxidant loss in fermented soy foods as a result of processing and storage under acid and oxygen might explain the beneficial effects of non-fermented soy foods on GC risk.(60–62) Another possible explanation is that fermented soy foods may contain nitroso compounds, thereby inducing gastric carcinogenesis.(63,64) Indeed, fermented soybean pastes have a high level of nitrate.(65) After we absorb dietary nitrate, 25% of it is secreted into the saliva and oral bacteria reduce approximately 5% to nitrite.(53) Since most saliva is swallowed, 80% of gastric nitrite in the normal acidic stomach comes from the reduction of ingested or endogenous nitrate.(66) Gastric nitrosation, which is carried out by nitrite, might produce unstable N-nitroso compounds that do not reach extra-gastric sites and act in the stomach to initiate GC, or may produce stable N-nitroso com-pounds that induce cancer at other sites.(66)

Soy food intake varies widely between Asian countries and Western countries(67) The amount of soy consumption is higher in Asian countries. For example, the amount of isoflavone consumption in Western countries averages <1 mg/day,(68,69) whereas it averages approximately 50 mg/day in Chinese and Japanese(38,70) populations. However, the incidence of GC is higher in Japan and Korea than in the USA and Europe. One of the important reasons for this is that Japanese and Korean populations consume more fermented soy foods than Americans and Europeans. However, it is known that soy is not the only plant food that provides isoflavones.(32) Isoflavones in Western diets stem from various other food sources.(71) Henceforth, some caution should be taken in associating isoflavone intake with soy food consumption.(32)

As seen above, the effects of fermented soy products might be confounded by salt intake, and the effects of non-fermented soy products might be confounded by vegetable and fruit intake(3,11) In almost all studies included in this meta-analysis, the possible confounding effects of salt, vegetable/fruits, and other dietary factors had not been considered in the soy product analysis(11) Moreover, the roles of salt, N-nitroso compounds, fruit/vegetable intake and other dietary factors have not been adjusted for in the majority of studies on soy food. Only age and sex were adjusted for in the analyses on soy foods.(3) We did not obtain information on infection with H. pylori, a major risk factor for GC,(11) and thus another potential confounding factor. H. pylori infection might be an intermediate factor between soy product intake and GC. These factors all need to be considered in future analyses on soy foods.

It is noted that there are some limitations regarding the interpretation of the meta-analysis. We selected a random-effect model in order to adjust for the effect of heterogeneity across studies, but this model does not discount the effects of heterogeneity. There is no change in the statistical significance of results obtained with a fixed-effect model and a random-effect model (overall summary OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.09–1.27, cohort studies OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.98–1.21, case–control studies OR = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.14–1.44 in the fixed-effect model for fermented soy food; overall summary OR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.70–0.84, cohort studies OR = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.81–1.08, case–control studies OR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.59–0.75 in the fixed-effect model for non-fermented soy food).

In addition, another bias occurs in this meta-analysis. Publication bias can cause researchers to reach incorrect conclusions from their meta-analyses because studies with statistically significant results tend to be published. The Begg’s test shows that there is no significant publication bias in this meta-analysis, but we could not ignore the possibility of this bias, inherent in any meta-analysis. Additionally, most studies were not planned to determine the effects of fermented or non-fermented soy foods on GC risk. Therefore, an outcome-reporting bias may have affected the validity of our meta-analysis.(72) Another limitation is the heterogeneity of the available data. Most studies were not designed to investigate soy foods, causing the quantification of soy intake and the extent to which confounding factors were adjusted to be different across studies in the meta-analysis.(32) The present study used a random-effect model for considering the heterogeneity in the calculation of summary statistics. How-ever, this limitation might complicate the interpretation of the results.(32) Therefore, the conclusions or interpretations made from the results of this meta-analysis should be considered cautiously due to the above limitations and biases.

In conclusion, the results of this meta-analysis show that a high intake of fermented soy foods is associated with an increased GC risk, whereas a high intake of non-fermented soy foods is associated with a decreased GC risk. These results might explain why GC incidence rates in Japan and Korea are high despite a high intake of soy foods. A high intake of non-fermented soy foods rather than fermented soy foods should help to reduce GC incidence rates in Japan and Korea.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Grant from National Cancer Center, Korea (0910221) and a Grant for the Third Term Comprehensive Control Research for Cancer from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Best,

Tan Kok Hui

Nutrition Made Simple, Life Made Rich

References

- Parkin DM. International variation. Oncogene 2004; 23: 6329–40.

- Ngoan LT, Mizoue T, Fujino Y, Tokui N, Yoshimura T. Dietary factors and stomach cancer mortality. Br J Cancer 2002; 87: 37–42.

- Wu AH, Yang D, Pike MC. A meta-analysis of soyfoods and risk of stomach cancer: the problem of potential confounders. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2000; 9: 1051–8.

- Messina MJ, Persky V, Setchell KD, Barnes S. Soy intake and cancer risk: a review of the in vitro and in vivo data. Nutr Cancer 1994; 21: 113–31.

- Kato I, Tominaga S, Ito Y et al. A prospective study of atrophic gastritis and stomach cancer risk. Jpn J Cancer Res 1992; 83: 1137–42.

- Inoue M, Tajima K, Kobayashi S et al. Protective factor against progression from atrophic gastritis to gastric cancer–data from a cohort study in Japan. Int J Cancer 1996; 66: 309–14.

- Galanis DJ, Kolonel LN, Lee J, Nomura A. Intakes of selected foods and beverages and the incidence of gastric cancer among the Japanese residents of Hawaii: a prospective study. Int J Epidemiol 1998; 27: 173–80.

- Tsugane S, Sasazuki S, Kobayashi M, Sasaki S. Salt and salted food intake and subsequent risk of gastric cancer among middle-aged Japanese men and women. Br J Cancer 2004; 90: 128–34.

- Sauvaget C, Lagarde F, Nagano J, Soda M, Koyama K, Kodama K. Lifestyle factors, radiation and gastric cancer in atomic-bomb survivors (Japan). Cancer Causes Control 2005; 16: 773–80.

- Tokui N, Yoshimura T, Fujino Y et al. Dietary habits and stomach cancer risk in the JACC Study. J Epidemiol 2005; 15(Suppl 2): S98–108.

- Nagata C, Takatsuka N, Kawakami N, Shimizu H. A prospective cohort study of soy product intake and stomach cancer death. Br J Cancer 2002; 87: 31–6.

- Khan MM, Goto R, Kobayashi K et al. Dietary habits and cancer mortality among middle aged and older Japanese living in Hokkaido, Japan by cancer site and sex. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2004; 5: 58–65.

- Kono S, Ikeda M, Tokudome S, Kuratsune M. A case-control study of gastric cancer and diet in northern Kyushu, Japan. Jpn J Cancer Res 1988; 79: 1067– 74.

- Kato I, Tominaga S, Ito Y et al. A comparative case-control analysis of stomach cancer and atrophic gastritis. Cancer Res 1990; 50: 6559–64.

- Hoshiyama Y, Sasaba T. A case-control study of stomach cancer and its relation to diet, cigarettes, and alcohol consumption in Saitama Prefecture, Japan. Cancer Causes Control 1992; 3: 441–8.

- Hoshiyama Y, Sasaba T. A case-control study of single and multiple stomach cancers in Saitama Prefecture, Japan. Jpn J Cancer Res 1992; 83: 937–43.

- Iwasaki J, Ebihira I, Uchida A, Ogura K. Case-control studies of lung cancer and stomach cancer cases in mountain villages and farming-fishing villages. J Jpn assoc rural med 1992; 41: 92–102.

- Inoue M, Tajima K, Hirose K, Kuroishi T, Gao CM, Kitoh T. Life-style and subsite of gastric cancer–joint effect of smoking and drinking habits. Int J Cancer 1994; 56: 494–9.

- Watabe K, Nishi M, Miyake H, Hirata K. Lifestyle and gastric cancer: a case-control study. Oncol Rep 1998; 5: 1191–4.

- Ito LS, Inoue M, Tajima K et al. Dietary factors and the risk of gastric cancer among Japanese women: a comparison between the differentiated and non-differentiated subtypes. Ann Epidemiol 2003; 13: 24–31.

- Machida-Montani A, Sasazuki S, Inoue M et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection and environmental factors in non-cardia gastric cancer in Japan. Gastric Cancer 2004; 7: 46–53.

- Lee JK, Park BJ, Yoo KY, Ahn YO. Dietary factors and stomach cancer: a case-control study in Korea. Int J Epidemiol 1995; 24: 33–41.

- Park H, Kim HS, Choi SY, Chung CK. Effect of dietary factors in the etiology of stomach cancer. Korean J Epidemiol 1998; 20: 82–101.

- Zhang YW, Eom SY, Kim YD et al. Effects of dietary factors and the NAT2 acetylator status on gastric cancer in Koreans. Int J Cancer 2009; 125: 139– 45.

- Kim HJ, Chang WK, Kim MK, Lee SS, Choi BY. Dietary factors and gastric cancer in Korea: a case-control study. Int J Cancer 2002; 97: 531–5.

- Kurosawa M, Kikuchi S, Xu J, Inaba Y. Highly salted food and mountain herbs elevate the risk for stomach cancer death in a rural area of Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 21: 1681–6.

- Hamada GS, Kowalski LP, Nishimoto IN et al. Risk factors for stomach cancer in Brazil (II): a case-control study among Japanese Brazilians in Sao Paulo. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2002; 32: 284–90.

- Lee SA, Kang D, Shim KN, Choe JW, Hong WS, Choi H. Effect of diet and Helicobacter pylori infection to the risk of early gastric cancer. J Epidemiol 2003; 13: 162–8.

- Ko KP, Park SK, Cho LY et al. Soybean product intake modifies the association between interleukin-10 genetic polymorphisms and gastric cancer risk. J Nutr 2009; 139: 1008–12.

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557–60.

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994; 50: 1088–101.

- Yan L, Spitznagel EL. Soy consumption and prostate cancer risk in men: a revisit of a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 89: 1155–63.

- Delaune A, Landreneau K, Hire K et al. Credibility of a meta-analysis: evidence-based practice concerning soy intake and breast cancer risk in premenopausal women. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2009; 6: 160–6.

- Yan L, Spitznagel EL. Meta-analysis of soy food and risk of prostate cancer in men. Int J Cancer 2005; 117: 667–9.

- Badger TM, Ronis MJ, Simmen RC, Simmen FA. Soy protein isolate and protection against cancer. J Am Coll Nutr 2005; 24: 146S–9S.

- Wu AH, Yu MC, Tseng CC, Pike MC. Epidemiology of soy exposures and breast cancer risk. Br J Cancer 2008; 98: 9–14.

- Yan L, Spitznagel EL, Bosland MC. Soy consumption and colorectal cancer risk in humans: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010; 19: 148–58.

- Trock BJ, Hilakivi-Clarke L, Clarke R. Meta-analysis of soy intake and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006; 98: 459–71.

- Myung SK, Ju W, Choi HJ, Kim SC. Soy intake and risk of endocrine-related gynaecological cancer: a meta-analysis. BJOG 2009; 116: 1697–705.

- Nagata C. Ecological study of the association between soy product intake and mortality from cancer and heart disease in Japan. Int J Epidemiol 2000; 29: 832–6.

- Wang H, Murphy P. Isoflavone content in commericial soybean foods. J Agric Food Chem 1994; 42: 1666–73.

- Cai Q, Wei H. Effect of dietary genistein on antioxidant enzyme activities in SENCAR mice. Nutr Cancer 1996; 25: 1–7.

- Mirvish SS. Inhibition by vitamins C and E of in vivo nitrosation and vitamin C occurrence in the stomach. Eur J Cancer Prev 1996; 5(Suppl 1): 131–6.

- Yanagihara K, Ito A, Toge T, Numoto M. Antiproliferative effects of isoflavones on human cancer cell lines established from the gastrointestinal tract. Cancer Res 1993; 53: 5815–21.

- Tatsuta M, Iishi H, Baba M, Yano H, Uehara H, Nakaizumi A. Attenutation by genistein of sodium-chloride-enhanced gastric carcinogesis induced by N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine in Wistar rats. Int J Cancer 1999; 80: 396–9.

- Nagata C. Factors to consider in the association between soy isoflavone intake and breast cancer risk. J Epidemiol 2010; 20: 83–9.

- Crane PS, Rhee SU, Seel DJ. Experience with 1,079 cases of cancer of the stomach seen in Korea from 1962 to 1968. Am J Surg 1970; 120: 747–51.

- Hirohata T, Kono S. Diet/nutrition and stomach cancer in Japan. Int J Cancer 1997; Suppl 10: 34–6.

- Lee HH, Wu HY, Chuang YC et al. Epidemiologic characteristics and multiple risk factors of stomach cancer in Taiwan. Anticancer Res 1990; 10: 875–81.

- Hu JF, Zhang SF, Jia EM et al. Diet and cancer of the stomach: a case-control study in China. Int J Cancer 1988; 41: 331–5.

- Ward MH, Lopez-Carrillo L. Dietary factors and the risk of gastric cancer in Mexico City. Am J Epidemiol 1999; 149: 925–32.

- You WC, Blot WJ, Chang YS et al. Diet and high risk of stomach cancer in Shandong, China. Cancer Res 1988; 48: 3518–23.

- Nan HM, Park JW, Song YJ et al. Kimchi and soybean pastes are risk factors of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11: 3175–81.

- Joossens JV, Hill MJ, Elliott P et al. Dietary salt, nitrate and stomach cancer mortality in 24 countries. European Cancer Prevention (ECP) and the INTERSALT Cooperative Research Group. Int J Epidemiol 1996; 25: 494– 504.

- Furihata C, Ohta H, Katsuyama T. Cause and effect between concentration-dependent tissue damage and temporary cell proliferation in rat stomach mucosa by NaCl, a stomach tumor promoter. Carcinogenesis 1996; 17: 401–6.

- Fox JG, Dangler CA, Taylor NS, King A, Koh TJ, Wang TC. High-salt diet induces gastric epithelial hyperplasia and parietal cell loss, and enhances Helicobacter pylori colonization in C57BL/6 mice. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 4823–8.

- Kodama K, Sumii K, Kawano M et al. Gastric juice nitrite and vitamin C in patients with gastric cancer and atrophic gastritis: is low acidity solely responsible for cancer risk? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003; 15: 987–93.

- Tsugane S, Akabane M, Inami T et al. Urinary salt excretion and stomach cancer mortality among four Japanese populations. Cancer Causes Control 1991; 2: 165–8.

- Tsugane S. Salt, salted food intake, and risk of gastric cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Sci 2005; 96: 1–6.

- Kaur C, Kapoor HC. Antioxidants in fruits and vegetables-the millennium’s health. Int J Food Sci Technol 2001; 36: 703–25.

- Lee Y, Park KY, Cheigh HS. Antioxidant effect of Kimchi with various fermentation period on the lipid oxidation of cooked ground meat. J Korean Soc Food Nutr 1996; 25: 261–6.

- Yalim S, Ozdemir Y. Effects of preparation procedures on ascorbic acid retention in pickled hot peppers. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2003; 54: 291–6.

- Correa P, Haenszel W, Cuello C, Tannenbaum S, Archer M. A model for gastric cancer epidemiology. Lancet 1975; 2: 58–60.

- Kato I, Tominaga S, Matsumoto K. A prospective study of stomach cancer among a rural Japanese population: a 6-year survey. Jpn J Cancer Res 1992; 83: 568–75.

- Seel DJ, Kawabata T, Nakamura M et al. N-nitroso compounds in two nitrosated food products in southwest Korea. Food Chem Toxicol 1994; 32: 1117–23.

- Mirvish SS. Role of N-nitroso compounds (NOC) and N-nitrosation in etiology of gastric, esophageal, nasopharyngeal and bladder cancer and contribution to cancer of known exposures to NOC. Cancer Lett 1995; 93: 17–48.

- Qin LQ, Xu JY, Wang PY, Hoshi K. Soyfood intake in the prevention of breast cancer risk in women: a meta-analysis of observational epidemiological studies. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2006; 52: 428–36.

- Peterson J, Lagiou P, Samoli E et al. Flavonoid intake and breast cancer risk: a case-control study in Greece. Br J Cancer 2003; 89: 1255–9.

- Horn-Ross PL, Hoggatt KJ, West DW et al. Recent diet and breast cancer risk: the California Teachers Study (USA). Cancer Causes Control 2002; 13: 407–15.

- Dai Q, Shu XO, Jin F et al. Population-based case-control study of soyfood intake and breast cancer risk in Shanghai. Br J Cancer 2001; 85: 372–8.

- Horn-Ross PL, Lee M, John EM, Koo J. Sources of phytoestrogen exposure among non-Asian women in California, USA. Cancer Causes Control 2000; 11: 299–302.

- Felson DT. Bias in meta-analytic research. J Clin Epidemiol 1992; 45: 885– 92.