This article was extracted and downloaded from circ.ahajournals.org

Association of Dietary Intake of Soy, Beans, and Isoflavones With Risk of Cerebral and Myocardial Infarctions in Japanese Populations

The Japan Public Health Center–Based (JPHC) Study Cohort I

Yoshihiro Kokubo, MD; Hiroyasu Iso, MD; Junko Ishihara, PhD; Katsutoshi Okada, MD; Manami Inoue, MD; Shoichiro Tsugane, MD; for the JPHC Study Group

Circulation is published by the American Heart Association. 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 72514

Background – Soy and isoflavones have been proposed to reduce the risk of cardiovascular risk factors, but their potential as preventatives for cardiovascular disease remains uncertain. We investigated the association of soy and isoflavone intake with risk of cerebral and myocardial infarctions (CI and MI).

Methods and Results – To examine the association of soy and isoflavone intake with the risk of CI and MI, we studied 40 462 Japanese (40 to 59 years old, without cardiovascular disease or cancer at baseline). They completed a food-frequency questionnaire (1990–1992) and received follow-up to 2002. After 503 998 person-years of follow-up, we documented incidence of CI (n=587) and MI (n=308) and of mortality for CI and MI combined (n=232). For women, the multivariable hazard ratios and 95% confidence limits for soy intake times per week versus 0 to 2 times per week were 0.64 (0.43 to 0.95) for risk of CI, 0.55 (0.26 to 1.09) for risk of MI, and 0.31 (0.13 to 0.74) for cardiovascular disease mortality. Similar but weaker inverse associations were observed between intake of miso soup and beans and risk of cardiovascular disease mortality. The multivariable hazard ratios for the highest versus the lowest quintiles of isoflavones in women were 0.35 (0.21 to 0.59) for CI, 0.37 (0.14 to 0.98) for MI, and 0.87 (0.29 to 2.52) for cardiovascular disease mortality. An inverse association between isoflavone intake and risk of CI and MI was observed primarily among postmenopausal women. No significant association of dietary intake of soy, miso soup, and beans and isoflavones with CI or MI was present in men.

Conclusions – High isoflavone intake was associated with reduced risk of CI and MI in Japanese women. The risk reduction was pronounced for postmenopausal women. (Circulation. 2007;116:2553-2562.)

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in developed and developing countries.1 Certain diets exhibit a major ability to modify risk factors for CVD. Evidence is increasing that the consumption of soy protein instead of animal protein lowers blood cholesterol levels and may lower the risk of CVD. A meta-analysis showed that the substitution of soy protein for animal protein significantly lowered total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides without affecting high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.3 Since then, well-controlled studies of soy protein and soy-derived isoflavones have demonstrated that the impact of soy protein consumption on LDL cholesterol levels was small.4,5 Dietary soy may be beneficial to cardiovascular health because of its high polyunsaturated fat, fiber, vitamin, and mineral content combined with its low saturated fat content.6

Received December 12, 2006; accepted September 14, 2007.

From the Department of Preventive Cardiology (Y.K.), National Cardiovascular Center, Osaka, Japan; Public Health (H.I.), Department of Social and Environmental Medicine, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan; Epidemiology and Prevention Division (J.I., M.I., S.T.), Research Center for Cancer Prevention and Screening, National Cancer Center, Tokyo, Japan; and Academic General Health Center (K.O.), University of Ehime, Ehime, Japan.

The online-only Data Supplement, consisting of tables, is available with this article at http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/ CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683755/DC1.

Correspondence to Yoshihiro Kokubo, MD, PhD, Department of Preventive Cardiology, National Cardiovascular Center, 5-7-1, Fujishiro-dai, Suita, Osaka, 565-8565 Japan; (E-mail ykokubo@hsp.ncvc.go.jp). Reprint requests to Shoichiro Tsugane, MD, Epidemiology and Prevention Division, Research Center for Cancer Prevention and Screening, National Cancer Center, 5-1-1 Tsukiji, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-0045, Japan; (E-mail stsugane@ncc.go.jp).

© 2007 American Heart Association, Inc.

Clinical Perspective p 2562

Many studies of soy intake have reported an impact on cardiovascular risk factors, notably on intermediate end points such as hyperlipidemia.3–5,7,8 However, only a few studies exist on the impact of soy intake on clinical end points such as CVD. A high dietary intake of isoflavones was associated with lower aortic stiffness in postmenopausal women.9 A prospective study of Japanese men and women, in whom average soy intake has been 10 to 70 times higher than in Western people,10,11 showed that soy intake was weakly and inversely associated with total mortality but not mortality due to CVD.12 In that study, the inverse association between dietary isoflavones and total mortality did not reach statistical significance after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors.12 A prospective study of Dutch women did not support the idea that dietary isoflavones lowered the risk of CVD.11 The quantity of isoflavones consumed by Dutch women, however, was quite small.11 Furthermore, no prospective study has examined a potential protective effect of isoflavone intake as an estrogen agonist on risk of CVD among postmenopausal women who have reduced blood estrogen concentrations.13 We hypothesize that the risk of cerebral infarction (CI) and myocardial infarction (MI) for postmenopausal Japanese women may be reduced through exposure to a large quantity of isoflavones, because estrogen receptors are not occupied with plasma estradiol in postmenopausal women.

Methods

Study Cohort

Cohort I of the Japan Public Health Center–Based (JPHC) Study was a population-based sample of 27 063 men and 27 435 women born between 1930 and 1949 (between 40 and 59 years old); it was registered in 14 administrative districts supervised by 4 public health center (PHC) areas on January 1, 1990. The present study included 12 291 subjects from Ninohe city and Karumai town in the Ninohe PHC area of Iwate prefecture; 15 782 subjects from Yokote city and Omonogawa town in the Yokote PHC area of Akita; 12 219 subjects from 8 districts of Minami-Saku county in the Saku PHC area of Nagano; and 14 206 subjects from Gushikawa city and Onna village in the Ishikawa PHC area of Okinawa.14 We excluded subjects who reported MIs, angina pectoris, strokes, or cancer before the study, which left a total of 40 462 men and women for the present analysis. The study was approved by the Human Ethics Review Committees of the National Cancer Center and the University of Tsukuba. Informed consent was obtained from each participant implicitly when they completed the baseline questionnaire in which the study purpose and follow-up were described.

Baseline Survey

A self-administered questionnaire was distributed to all registered noninstitutional residents in 1990, asking them to report on their demographic characteristics, medical history, smoking habits, drink-ing habits, and diet. Of these, 40 462 men and women (74.2%) returned their questionnaires between January 1990 and May 1992, primarily between February and October 1990.

The 1990 food-frequency questionnaire included 44 foods with 3 questions to assess soy, bean, and miso consumption. The 1995 follow-up questionnaire covered 147 foods with 8 questions on soy products.15 Each participant was asked how often he or she had consumed soy, miso soup, and beans on average during the previous month. Portion size for each food was specified in the 1995 questionnaire but not in the 1990 questionnaire. Responses for each food item ranged from “rarely” to “1 to 2 days per week,” “3 to 4 days per week,” and “almost every day” in the 1990 questionnaire. For the 1995 questionnaire, possible responses were “rarely,” “1 to 3 times per month,” “1 to 2 times per week,” “3 to 4 times per week,” “5 to 6 times per week,” “once per day,” “2 to 3 times per day,” “4 to 6 times per day,” and “7 or more times per day.” Study participants who answered “almost daily or more frequently” were asked an additional question about the average number of bowls of miso soup consumed per day.

Isoflavone intake was calculated from these 2 questions with a portion size of 100 mL for miso soup (10 g of miso paste, 2.9 mg of genistein, and 2.1 mg of daidzein) and 60 g for soy foods (18.4 mg of genistein and 10.9 mg of daidzein).16 Total isoflavone intake was defined for the present study as the sum of genistein and daidzein intake. Portion size and isoflavone contents were validated through a study in which 247 subjects provided 28-day dietary records accompanied by blood and urine samples.16,17 The correlation coefficients between these 2 questionnaires and participants’ dietary records were 0.59 for genistein and 0.60 for daidzein, and the correlation coefficients between repeated measurements were >0.7.16 Estimated mean intakes were 30% higher as assessed by the questionnaires (mean±SD 18.3±13.1 mg for daidzein and 31.4±24 mg for genistein) than by the dietary records (mean±SD 14.5±6.6 mg for daidzein and 23.4±10.5 mg for genistein). The associations for miso soup consumption frequency, soy food consumption frequency, and estimated isoflavone intake between the 2 questionnaires administered 5 years apart were 0.70, 0.53, and 0.61, respectively.18 Information on the consumption of isoflavone supplements was not requested in the 1990 questionnaire. At that time, isoflavone supplements were assumed to be used infrequently. Menopausal status was questioned in the baseline questionnaire in the form of alternatives: premenopause, postmenopause, or surgical menopause.

Stroke and MI: Confirmation and Classification of Stroke Subtypes

A total of 30 hospitals in the 4 PHC areas were capable of performing computed tomography scans and/or magnetic resonance imaging. By region, that included 10 hospitals in the Ninohe PHC area, 4 in the Yokote PHC area, 3 in the Saku PHC area, and 14 in the Ishikawa PHC area. All were major hospitals at which acute stroke and MI cases would be admitted. Medical records were reviewed by registered hospital workers, PHC physicians, or re-search physicians who did not have access to lifestyle data. Stroke and MI events were registered if they occurred after the date on which the baseline questionnaire was received and before January 1, 2003. To complete the surveillance for fatal stroke and MI, we also conducted a systematic search for death certificates. For all fatal strokes and MIs listed on the death certificates but that had not been registered, medical records in registered hospitals were reviewed by hospital workers, PHC physicians, or research physicians. We regarded these fatal CIs and MIs as probable CIs and MIs, respectively. Details on the surveillance procedures have been described elsewhere.19,20

Strokes were confirmed according to National Survey of Stroke criteria. These criteria require the rapid onset of a constellation of neurological deficits that lasts at least 24 hours (or until death). For each stroke subtype (ie, ischemic stroke [thrombotic or embolic stroke], intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage), a definite diagnosis was established on the basis of the examination of computed tomography scans, magnetic resonance imaging results, or autopsies.21 MI was confirmed in the medical records according to the criteria of the MONICA project (MONitoring of trends and determinants In CArdiovascular disease), which requires evidence from ECGs, cardiac enzymes, and/or autopsy.22 Information on the underlying cause of death was obtained by checking against death certificate files with permission to confirm mortality due to CI and MI (ischemic CVD) according to the International Classification of Death, 10th Revision codes I21–I23 and I46 for MI and I60–I61, I63, and I693 for CI.

Changes in residential status were identified through the residential registry in each area. Subjects who moved from their original residence (2% of total participants) were censored at that time.

Statistical Analysis

ANOVAs and 2 tests were used to compare mean values and frequencies according to the frequency of dietary soy intake by sex. Time-dependent Cox proportional hazards regression models were used for the association of soy, miso soup, beans, and isoflavones with CI and MI separately for men and women during the 13-year follow-up (from 1990 until the end of 2002). For each subject, person-months of follow-up were calculated from January 1, 1990, to whichever came first: the first end point, death, emigration, or December 31, 2002.

Table 1. Sex-Specific Baseline Distributions of CVD Risk Factors and Selected Dietary Variables in a Cohort of 40 462 Men and Women According to the Frequency of Dietary Soy Intake at the Baseline Surveillance

*ANOVA or x2 tests were performed.

The time-dependent Cox proportional hazards regression was fitted on the grouped or categorized consumption (reference group was the lowest consumption level) after adjustment for age and other potential confounding factors, which were the baseline age values (in 5-year categories); sex; smoking status (never, ex-smoker, and current smoker of 1 to 19 or .20 cigarettes per day); alcohol intake (nondrinkers [<1 day per month], occasional drinkers [1 to 3 days per month], or weekly ethanol intake of 1 to 149 g, 150 to 299 g, 300 to 449 g, and .450 g); body mass index (in quintiles); history of hypertension or diabetes mellitus (yes or no); medication use for hypercholesterolemia (yes or no); quintiles of energy-adjusted dietary intake of fruits, vegetables, and salt; education levels (junior high school, high school, and college or higher); leisure time spent engaged in sports (<1 day per month, 1 to 3 days per month, and day per week); and nearest PHC. We updated the quintiles for dietary intake and the confounding factors (except for age, sex, education level, and PHC) using the 5-year follow-up questionnaire, to which 80% of the baseline participants responded.20 Trend tests were conducted by assignment for frequencies of soy, bean, and miso soup intake and estimated values for isoflavones consumption to test the significance of these variables. We excluded women with surgical menopause from the stratified analysis by menopausal status because the presence or absence of estrogen exposure was uncertain. In addition, isoflavone and menopause (or sex) interactions were tested with use of a cross-product term of isoflavone intake with sex or menopausal status. All statistical analyses were conducted with the SAS statistical package (release version 8.2, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

The authors had full access to and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Results

During a follow-up period that averaged 12.5 years, 1230 strokes were documented, of which 1137 were confirmed through imaging or autopsy. These results for strokes comprised 587 CIs, 437 intracerebral hemorrhages, and 206 subarachnoid hemorrhages. In addition, 308 MIs were documented, of which 232 were definite MI on the basis of clinical or autopsy evidence, and 23 were cases of sudden cardiac death.

Table 2. Sex-Specific, Age-Adjusted, and Multivariable HRs (95% CLs) for the Incidence of CI and MI According to Dietary Intakes of Soy, Miso Soup, and Beans on the Baseline Questionnaire.

Multivariable HRs were adjusted for age; sex; smoking; alcohol use; body mass index; history of hypertension or diabetes mellitus; medication use for hypercholesterolemia; education level; sports; dietary intake of fruits, vegetables, fish, salt, and energy; menopausal status for women; and PHC.

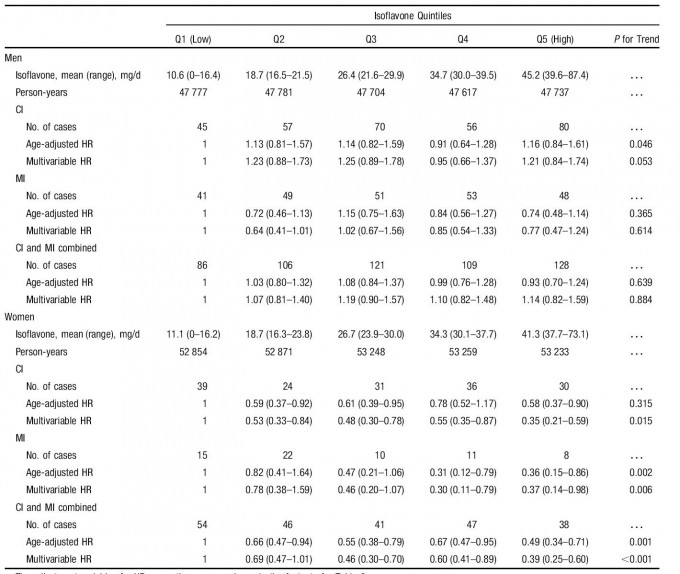

Table 3. Sex-Specific, Age-Adjusted, and Multivariable HRs (95% CLs) for the Incidence of CI and MI According to Dietary Intake of Isoflavones.

The adjustment variables for HRs were the same as shown in the footnote for Table 2.

Table 1 shows CVD risk factors and the intake of selected nutrients and foods, according to the frequency of dietary soy intake. The variables, except for age, were updated according to the 5-year follow-up survey. Compared with persons who ate soy 0 to 2 days per week, on average, those who ate more soy were slightly older and had a lower education level. Those who consumed more soy were also less likely to be current smokers but more likely to be hypertensive, and men in this category were more likely to have diabetes mellitus. The frequency of soy intake was positively associated with total energy intake and with mean daily intake of rice, vegetables, fruits, fish, potassium, calcium, carbohydrate, polyunsaturated fatty acid, saturated fatty acid, fiber, and isoflavones for both sexes. Similar trends were observed according to the frequencies of intake of dietary miso soup and beans.

Table 2 presents hazard ratios (HRs) for the incidence of CI and MI according to the frequencies of dietary intake of soy, miso soup, and beans at the baseline questionnaire. The multivariable HR (95% confidence limits [CLs]) for those who consumed soy foods ~5 days per week compared with 0 to 2 days per week was 0.64 (0.43 to 0.95, P for trend=0.037) for CI, 0.55 (0.26 to 1.09, P for trend=0.098) for MI, and 0.71 (0.49 to 1.01, P for trend=0.065) for CI and MI combined in women. When we removed potential biological mediators (ie, histories of hypertension and diabetes mellitus and medication use for hypercholesterolemia) from the adjusted variables, we found a weaker but significant inverse association between soy intake and risk of CI and MI combined (Appendix Iin the online-only Data Supplement). Similar but weaker inverse associations were observed between intake of miso soup and beans and risk of CI and MI combined. No significant association of dietary intake of soy, miso soup, and beans and isoflavones with CI or MI was present in men.

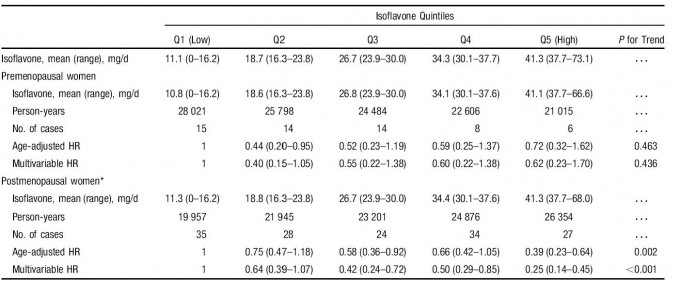

Table 4. Age-Adjusted Multivariable HRs (95% CLs) of the Incidence of Ischemic CVD According to Dietary Intake of Isoflavones by Menopausal Status in Women.

The adjustment variables for HRs were the same as shown in the footnote for Table 2. *Women with surgical menopause were excluded from the analysis.

Table 3 presents HRs for the incidence of CI and MI by quintile of isoflavone intake. An inverse association existed between isoflavone intake and risk of CI and MI in women but not in men. That inverse association became more pronounced after adjustment for confounding variables, in particular, histories of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, and the sex interaction was highly statistically significant (P<0.001). The multivariable HRs (95% CLs) for the highest quintile (37.7 to 73.1 mg/d) referenced to the lowest quintile (0 to 16.2 mg/d) of isoflavone intake were 0.35 (0.21 to 0.59, P for trend=0.015) for CI, 0.37 (0.14 to 0.98, P for trend=0.006) for MI, and 0.39 (0.25 to 0.60, P for trend <0.001) for CI and MI combined. When we removed the potential biological mediators, we found a weaker but signif-icant inverse association between isoflavone intake and risk of CI and MI combined (Appendix II in the online-only Data Supplement). The inverse association for CI and MI combined was more pronounced in postmenopausal women than in premenopausal women, and the interaction with menopausal status was statistically significant (P=0.046; Table 4).

Table 5 presents HRs for ischemic CVD mortality accord-ing to the frequencies of dietary intake of soy, miso, and beans reported on the baseline questionnaire. The multivari-able HR (95% CL) for those who consumed soy foods ~5 days per week compared with 0 to 2 days per week was 0.31 (0.13 to 0.74, P for trend=0.006) for ischemic CVD mortality in women, but no association was found in men. No significant associations between intake of miso soup and beans and ischemic CVD mortality were present in either men or women.

Table 5. Sex-Specific, Age-Adjusted, Multivariable HRs (95% CLs) of Ischemic CVD Mortality According to Dietary Intake of Soy, Miso Soup, and Beans on the Baseline Questionnaire.

The adjustment variables for HRs were the same as shown in the footnote for Table 2.

Table 6. Sex-Specific, Age-Adjusted, Multivariable HRs (95% CLs) of Ischemic CVD Mortality According to Dietary Intake of Isoflavones.

The adjustment variables for HRs were the same as shown in the footnote for Table 2. *Incalculable due to the small number of cases.

An inverse association existed between isoflavone intake and ischemic CVD mortality in women but not in men (Table 6). The multivariable HR (95% CL) of ischemic CVD mortality for the highest to second highest versus the lowest quintiles was 0.17 (0.04 to 0.78, P for trend=0.053).

Discussion

In the present study of middle-aged Japanese subjects, we found a significant inverse association between soy and isoflavone intake with the risk of incidence for CI and MI in women but no association in men. The inverse association was primarily observed in postmenopausal women. We also found a significant inverse association of soy intake with the risk of mortality for ischemic CVD in women. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time such results, for both the incidence of and mortality due to CVD, have been observed in a cohort study.

Soy is the major source of isoflavones in food, with the primary dietary isoflavones being genistein, daidzein, and glycetein.23 Soy isoflavones can act as antioxidants, reducing the formation of oxidized lipoproteins like LDL.8 Several articles have shown the reduced oxidative potential of serum in subjects who consume soy protein.7,8 Isoflavones are structurally similar to estrogens and bind to the estrogen receptor, so it is biologically plausible that they protect against development of atherosclerosis as estrogen ago-nists.13,24 We observed a significant risk reduction of CI and MI in the ~2nd and ~3rd quintiles of isoflavone intake (~18 and ~26 mg/d, respectively) in women. The intake of isoflavones in the 2nd quintile was 20 times greater than the mean levels of isoflavone intake in Westerners.25 In premenopausal women, estradiol receptors could be occupied with plasma estradiol to a greater extent than in postmenopausal women; therefore, postmenopausal women may benefit more from intake of isoflavones.13

Soy contains high polyunsaturated fat (eg, linoleic acid and vitamin E).2,10 The mechanism by which serum linoleic acid reduces the risk of MI was primarily related to its serum cholesterol–lowering effect.26 The mechanism for the risk of CI is not clear27 but could be 1 of the following: dietary intake of linoleic acid may lower blood pressure28; it may lower total cholesterol levels29; or it may improve glucose tolelance.30 Soy also contains vitamin E, which may help protect against MI31 and fatal stroke.32 Soy also contains n-3 fatty acids, which have been associated with a reduced risk of CVD in several studies.33,34

Isoflavones have been the subject of multiple lines of research to identify their impact in terms of their hypocho-lesterolemic effects,3,35–38 antioxidant effects,8 blood pres-sure–lowering effect,39 and estrogen-like effects13,40 on blood vessels. A meta-analysis of 38 controlled clinical studies concluded that daily soy protein consumption resulted in a 9.3% decrease in total serum cholesterol, a 12.9% decrease in LDL cholesterol, and a 10.5% decrease in triglycerides, which are risk factors for coronary heart disease, among hypercholesterolemic subjects but not among subjects with low or normal cholesterol levels.3 Three recent meta-analyses of the effect of soy protein–containing isoflavones have shown a similar but weak effect. However, the association of soy and isoflavone consumption with a reduced risk of CI may not reflect a direct relationship with the effect of reducing cholesterol levels, because the contribution of hypercholesterolemia to the risk of CI has been weak and inconsistent.41–44 A study by Ruiz-Larrea et al45 showed that genistein, the most potent antioxidant of isoflavones in soy protein, enhances resistance of LDL cholesterol to oxidation.

Soy protein with isoflavones might lower blood pressure, unlike casein or milk protein, but only 1 study has shown a significant decrease in blood pressure as a result of consuming soy protein.39 Most studies indicate that soy and isofla-vones do not significantly affect blood pressure.6

The present study showed that an increased intake of miso soup by women was associated with a reduced incidence of CI, despite the fact that miso is a major source of salt for most Japanese people. Previous studies have indicated that a higher salt intake increases blood pressure,46,47 which leads to a higher risk of stroke.48 Miso soup, however, contains tofu, seaweed, and vegetables, among other ingredients, which may reduce the likelihood of ischemic CVD.2

The present study has some methodological strengths compared with previous studies. We evaluated a large prospective cohort enrolled from the Japanese general population. A prospective study has little recall bias, and results from a cohort of general population are more relevant than those of occupational, hospital-based volunteers. We examined the risk of stroke and MI incidence and mortality. Incidence is a more direct measure of stroke and MI risk than death, because the time to CVD death is influenced by treatment. We estimated isoflavone intake using a validated questionnaire. Our sample came from Japanese populations with a large variation in consumption of isoflavones. Associations between exposure and disease can be detected more easily when exposure is variable. Median isoflavone intake among all study participants was 7 times higher than that among Chinese in Singapore49 and 70 times higher than that among Dutch women.11 The present study cohort was established in 1990, and thus, we supposed the percentage of isoflavone supplement users to be nearly zero. Finally, we examined menopausal status in the present study, and thus, we could analyze the association of isoflavone intake and incidence of CI and MI stratified by menopausal status.

The present study has several limitations. First, the data for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and other health conditions were self-reported. These self-reported variables may present a problem with potential misclassification; however, the self-reported data for hypertension and diabetes mellitus may be reasonably accurate, because nationwide annual health screenings have been conducted since 1992 in Japan.50 Residual and immeasurable confounding is a potential limitation in the present study. No blood pressure measurements or biochemical markers were used in the present study; however, the existence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus was determined from the questionnaires at the baseline survey. Second, measurement errors with nutrient intake are inevitable; however, the reproducibility for soy intake measurements in the baseline and 5-year follow-up questionnaire was good and was compatible with the results reported in the Nurses’ Health Study.33 In the present study, any errors are likely nondifferential and would attenuate associations with soy and isoflavone intake toward a null value. Third, the generalizability to other ethnic groups is uncertain, because few other populations have a large variation of isoflavone intake that allows the examination of an association between isoflavones and disease. Fourth, because we studied dietary intake of isoflavones, the present results are not relevant to the association of isoflavone supplement use with ischemic CVD.

In conclusion, the present community-based prospective study showed that high consumption of isoflavones was associated with a reduced risk of CI and MI among women, particularly postmenopausal women. Our results suggest that the consumption of dietary isoflavones may be beneficial to postmenopausal women for the prevention of ischemic CVD.

Appendix

Study Investigators

The investigators and participating institutions for cohort I of the JPHC Study, a part of the JPHC Study Group (Principal Investigator: S. Tsugane), were as follows: S. Tsugane, T. Hanaoka, M. Inoue, and T. Sobue, Epidemiology and Prevention Division, National Cancer Center, Tokyo; J. Ogata, S. Baba, T. Mannami, Y. Kokubo, and A. Okayama, Division of Preventive Cardiology, National Cardiovascular Center, Osaka; K. Miyakawa, F. Saito, A. Koizumi, Y. Sano, and I. Hashimoto, Iwate Prefectural Ninohe Public Health Center, Ninohe; Y. Miyajima, N. Suzuki, S. Nagasawa, and Y. Furusugi, Akita Prefectural Yokote Public Health Center, Yokote; H. Sanada, Y. Hatayama, F. Kobayashi, H. Uchino, Y. Shirai, T. Kondo, R. Sasaki, and Y. Watanabe, Nagano Prefectural Saku Public Health Center, Saku; Y. Kishimoto, E. Takara, M. Kinjo, T. Fukuyama, and M. Irei, Okinawa Prefectural Ishikawa Public Health Center, Ishikawa; S. Matsushima and S. Natsukawa, Saku General Hospital, Usuda; S. Watanabe and M. Akabane, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Tokyo; M. Konishi and K. Okada, Ehime Uni-versity, Matsuyama; S. Tominaga, Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute, Nagoya; M. Iida and W. Ajiki, Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases, Osaka; S. Sato, Osaka Medical Center for Health Science and Promotion, Osaka; the late M. Yamaguchi, Y. Matsumura, and S. Sasaki, National Institute of Health and Nutrition, Tokyo; Y. Tsubono, Tohoku University, Sendai; H. Iso and Y. Honda, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba; H. Sugimura, Hamamatsu University, Hamamatsu; M. Kabuto, National Institute for Environmental Studies, Tsukuba; N. Yasuda, Kochi Medical School; S. Kono, Kyushu University, Fukuoka; K. Suzuki, Research Institute for Brain and Blood Vessels–Akita, Akita; Y. Takashima, Kyorin University, Tokyo; and E. Maruyama, Kobe University, Kobe.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all staff members in each study area and the central office for their painstaking efforts to conduct the baseline survey and follow-up research.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by grants-in-aid for Cancer Research and the Third-Term Comprehensive Ten-Year Strategy for Cancer Control from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan.

Disclosures

None.

Best,

Tan Kok Hui

Nutrition Made Simple, Life Made Rich

References

- Krauss RM, Eckel RH, Howard B, Appel LJ, Daniels SR, Deckelbaum RJ, Erdman JW Jr, Kris-Etherton P, Goldberg IJ, Kotchen TA, Lichtenstein AH, Mitch WE, Mullis R, Robinson K, Wylie-Rosett J, St Jeor S, Suttie J, Tribble DL, Bazzarre TL. AHA dietary guidelines: revision 2000: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2000;31:2751–2766.

- Weggemans RM, Trautwein EA. Relation between soy-associated isoflavones and LDL and HDL cholesterol concentrations in humans: a meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:940–946.

- Sacks FM, Lichtenstein A, Van Horn L, Harris W, Kris-Etherton P, Winston M. Soy protein, isoflavones, and cardiovascular health: an American Heart Association Science Advisory for professionals from the Nutrition Committee. Circulation. 2006;113:1034–1044.

- Clair RS, Anthony M. Soy, isoflavones and atherosclerosis. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2005;301–323.

- Erdman JW Jr. AHA Science Advisory: soy protein and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the AHA. Circulation. 2000;102:2555–2559.

- Nagata C, Takatsuka N, Shimizu H. Soy and fish oil intake and mortality in a Japanese community. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:824–831.

- Tsugane S, Fahey MT, Sasaki S, Baba S. Alcohol consumption and all-cause and cancer mortality among middle-aged Japanese men: seven-year follow-up of the JPHC study cohort I: Japan Public Health Center. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:1201–1207.

- Yamamoto S, Sobue T, Sasaki S, Kobayashi M, Arai Y, Uehara M, Adlercreutz H, Watanabe S, Takahashi T, Iitoi Y, Iwase Y, Akabane M, Tsugane S. Validity and reproducibility of a self-administered food-frequency questionnaire to assess isoflavone intake in a Japanese population in comparison with dietary records and blood and urine isoflavones. J Nutr. 2001;131:2741–2747.

- Yamamoto S, Sobue T, Kobayashi M, Sasaki S, Tsugane S. Soy, isoflavones, and breast cancer risk in Japan. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003; 95:906–913.

- Iso H, Kobayashi M, Ishihara J, Sasaki S, Okada K, Kita Y, Kokubo Y, Tsugane S. Intake of fish and n3 fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease among Japanese: the Japan Public Health Center-Based (JPHC) Study Cohort I. Circulation. 2006;113:195–202.

- Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Amouyel P, Arveiler D, Rajakangas AM, Pajak A. Myocardial infarction and coronary deaths in the World Health Organization MONICA Project: registration procedures, event rates, and case-fatality rates in 38 populations from 21 countries in four continents. Circulation. 1994;90:583–612.

- Anthony MS, Clarkson TB, Williams JK. Effects of soy isoflavones on atherosclerosis: potential mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68: 1390S–1393S.

- Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Wolk A, Colditz GA, Hennekens CH, Willett WC. Dietary intake of alpha-linolenic acid and risk of fatal ischemic heart disease among women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:890–897.

- Iacono JM, Puska P, Dougherty RM, Pietinen P, Vartiainen E, Leino U, Mutanen M, Moisio S. Effect of dietary fat on blood pressure in a rural Finnish population. Am J Clin Nutr. 1983;38:860–869.

- Salomaa V, Ahola I, Tuomilehto J, Aro A, Pietinen P, Korhonen HJ, Penttila I. Fatty acid composition of serum cholesterol esters in different degrees of glucose intolerance: a population-based study. Metabolism. 1990;39:1285–1291.

- Yochum LA, Folsom AR, Kushi LH. Intake of antioxidant vitamins and risk of death from stroke in postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:476–483.

- Lemaitre R, King I, Mozaffarian D, Kuller L, Tracy R, Siscovick D. n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids, fatal ischemic heart disease, and nonfatal myocardial infarction in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:319–325.

- Crouse JR III, Morgan T, Terry JG, Ellis J, Vitolins M, Burke GL. A randomized trial comparing the effect of casein with that of soy protein containing varying amounts of isoflavones on plasma concentrations of lipids and lipoproteins. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2070–2076.

- Pelletier X, Belbraouet S, Mirabel D, Mordret F, Perrin JL, Pages X, Debry G. A diet moderately enriched in phytosterols lowers plasma cholesterol concentrations in normocholesterolemic humans. Ann Nutr Metab. 1995;39:291–295.

- Honore EK, Williams JK, Anthony MS, Clarkson TB. Soy isoflavones enhance coronary vascular reactivity in atherosclerotic female macaques. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:148–154.

- Tanizaki Y, Kiyohara Y, Kato I, Iwamoto H, Nakayama K, Shinohara N, Arima H, Tanaka K, Ibayashi S, Fujishima M. Incidence and risk factors for subtypes of cerebral infarction in a general population: the Hisayama study. Stroke. 2000;31:2616–2622.

- Lindenstrom E, Boysen G, Nyboe J. Influence of total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides on risk of cere-brovascular disease: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. BMJ. 1994; 309:11–15.

- Appel LJ, Espeland MA, Easter L, Wilson AC, Folmar S, Lacy CR. Effects of reduced sodium intake on hypertension control in older individuals: results from the Trial of Nonpharmacologic Interventions in the Elderly (TONE). Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:685–693.

- Tuomilehto J, Jousilahti P, Rastenyte D, Moltchanov V, Tanskanen A, Pietinen P, Nissinen A. Urinary sodium excretion and cardiovascular mortality in Finland: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;357:848– 851.

- Kawada T, Suzuki S. Validation study on self-reported height, weight, and blood pressure. Percept Mot Skills. 2005;101:187–191.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE

Dietary soy may be beneficial for cardiovascular health because of its high polyunsaturated fat, fiber, vitamin, and mineral content combined with its low saturated fat content; however, few studies have examined the associations of soy and isoflavone intake with risk of cardiovascular disease in terms of both incidence and mortality. Because the Japanese diet is rich in soy, a cohort study of Japanese individuals was warranted.

We studied 40 462 Japanese men and women aged 40 to 59 years who were free of cardiovascular disease or cancer at baseline and who answered a food-frequency questionnaire. They were followed up for 12 years to investigate the associations of soy and isoflavone intake with risks of cerebral and myocardial infarction incidence and cardiovascular disease mortality. Soy intake ~5 times per week versus 0 to 2 times per week was associated with 36% and 69% reduced risks of cerebral infarction incidence and cardiovascular disease mortality in women, respectively. The highest (41 mg/d) versus lowest (11 mg/d) quintile of isoflavone intake was associated with an 65% reduced risk of cerebral and myocardial infarction incidence in women. The inverse association of isoflavone intake with risks of cerebral and myocardial infarction incidence was observed primarily among postmenopausal women.

No significant association between soy and isoflavone intake and risk of ischemic cardiovascular disease was present in men. Our results suggest that the consumption of dietary isoflavones may be beneficial for postmenopausal women for the prevention of ischemic cardiovascular disease.

Appendix A. Multivariable HRs (95% CLs) of Incidence for CI and MI. According to Dietary intake of Soy, Miso-soup, and Bean at the Baseline Questionnaire.

Multivariable HRs were adjusted for age, sex, smoking, alcohol, BMI, education levels, sports, dietary intake of fruits, vegetables, fish, salt, and energy, menopausal status for women, and PHC.

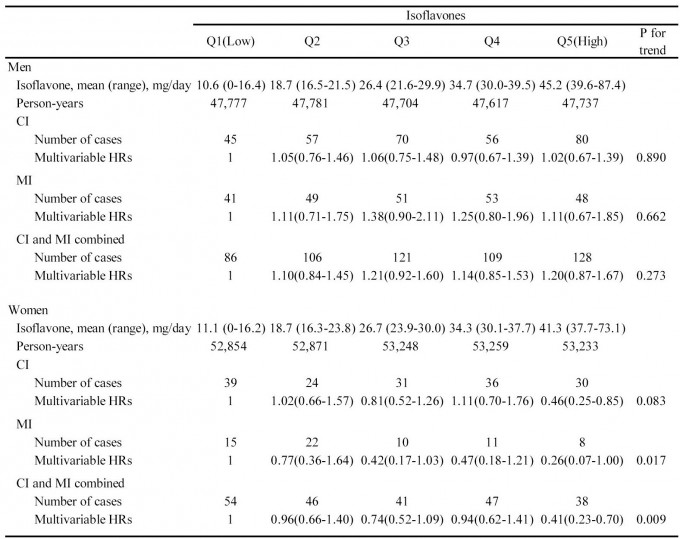

Appendix B. Sex-specific Age-adjusted and Multivariable HRs (95% CLs) of Incidence for CI and MI According to Dietary Intake of Isoflavones.

The adjustment variables for HRs were the same as shown in the footnote of Appendix A.